Sara Stratton

Trinity St. Paul’s and Bloor Street United Churches

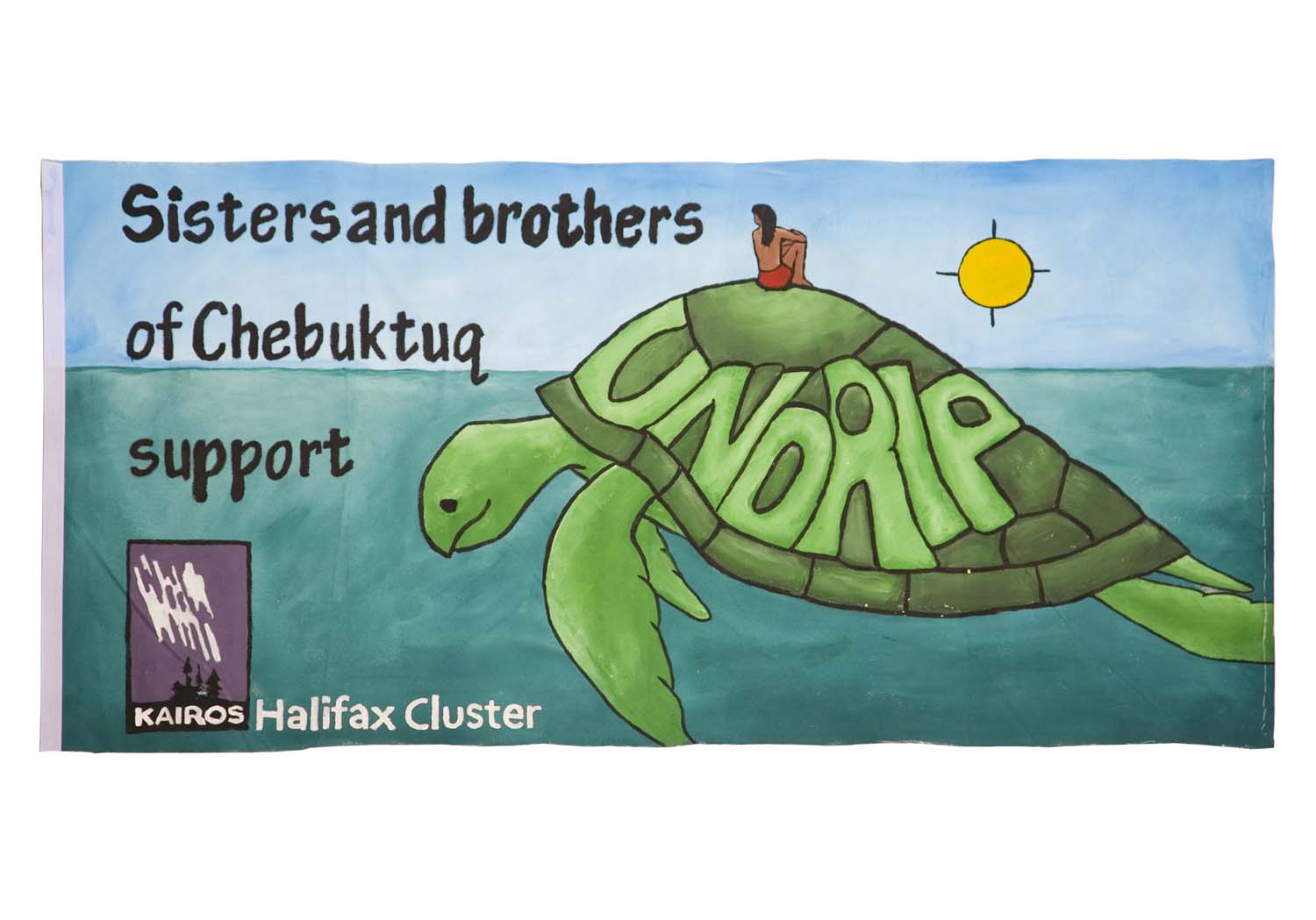

For the last 18 months or so, the biggest part of my job with the Canadian Ecumenical Jubilee Initiative has been in the area of indigenous justice. Together with the Aboriginal Rights Coalition, we have been running an education and advocacy campaign focussed on a new way for us, as a nation, to approach the land and resource rights that are inherent to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. In seeking this new approach, which has at its heart the full recognition of the human rights of aboriginal peoples, we are seeking a new relationship between aboriginal and non-aboriginal peoples in Canada. This is not something that you do overnight, easily, or without resistance.

It’s a process built slowly on education and empowerment. We have spent the better part of a year doing that work, in partnership with Aboriginal peoples across the country. One of our biggest tasks was to revisit history and understand the roots of our current relationship. It is a relationship and a history built on the dispossession of Aboriginal peoples from the land. We learned this history through something called the blanket exercise. Blankets are laid out, representing North America before the arrival of the Europeans. Workshop participants stand on the blankets. Then a European arrives and a process begins whereby people are removed from the blankets by war, disease, trickery and legislation. As history is related, the blankets become smaller and smaller, and are isolated from each other. We finally end up with a few little piles of blankets with peoples stranded on them. Dispossession is complete. What was once a source of comfort, livelihood, and spirituality –the blankets, the land– has been taken away.

Recently we wanted an opportunity to highlight this work, to have a series of media and community action moments across Canada and, ultimately, in Ottawa. We decided to reverse the blanket exercise on the grounds of the Supreme Court, and to do so using blankets which we gathered from communities across the country on a 5 day train trip from the four directions. The train would not go as far East as Canada goes –there are no trains in Newfoundland– but neither did it go as far West as Tofino or as far North as Pond Inlet. It did go just about as far South as you can go in Canada – Windsor.

When we first came up with the idea of the blanket train, I knew I wanted to ride it. And so I volunteered to be the national staff contact on the Eastern train. As the dates for my journey drew nearer, I began to grow more apprehensive about the trip. I worried about logistical details but I also worried about how I would cope, having to travel with people I had never met and get off in communities along the way to collect blankets from people I only knew as an email address or voice on the telephone. They would know me only by my bright red “blanket train engineer” t-shirts which I was not even sure I liked! I did not know whether we would meet with violence in areas such as New Brunswick, where tensions between aboriginal and non-aboriginal peoples run high these days. I worried about indifference. I did not know what to expect on this journey. I was apprehensive about it, and I felt guilty about my apprehension. After all, I was a professional justice-seeker. I have been to rallies, workshops, summits, government meetings, and demonstrations galore. What’s so scary about a train ride?

I will ruin the end of the story and tell you that it was an incredible ride, and an incredible moment on the Supreme Court grounds where we laid out more than 1000 blankets. I have yet to find the words to really describe it. What I do have are some stories of the people I met, and the journey we made together.

Cornwallis Park in Halifax, just across from the VIA station. Betty Peterson, a local activist and Raging Grannie, has pulled together the event. She expects 30 or 40 blankets; we leave with twice that many. One of them, a quilt from an Anglican parish in Fall River, is hand-delivered by a woman who, at first glance, is about the last I’d expect to see in a church and one of the first I’d think would complain about “those damned Indians.” At the end when I thank her for the blanket, she refers to the gathering, “isn’t this the thanks? How could I not do this?”

Moncton: a huge crowd at the station. 30 boxes of blankets already stowed as cargo. The Chief and many people from Big Cove have worked together with the local Jubilee and Ten Days groups to plan this event. They hold a purification ceremony and blessing on the train platform. I have to get back on the train before it is all complete; a woman from Big Cove sees this and cuts across to reach me, she takes my hand and passes me a quilt that she and other women and girls from Big Cove have made. She looks me straight in the eye and says, “Now you take care of our blanket.” I think I nod assent. Then it is onto the train, where the steward has opened the top half of the door and beckons me to “wave goodbye to your people.” Another woman from Big Cove yells, “I like your shirt!” This is the shirt about which I was so ambivalent. “Can I have it?” I laugh out loud, “I can’t take off my shirt!” I have one more in my luggage; it’s for gkisedtanamoogk, ARC-Atlantic’s co-chair, whom I’m meeting in 2 hours in Miramichi. I figure he won’t mind; I get it and call to the woman as the train is just about to leave the station. I throw it to her and a great cheer goes up, hands wave in the sun, and we are gone. By now I’m beginning to really like the shirt.

I go back to my compartment and open up the quilt I’ve been given; it is decorated with pictures and signed with names. The lower left hand corner grabs my attention; a drawing of a dream catcher and written in an unsure hand below, “make my dreams come true.” First, the commandment given when the blanket was passed on to me and now this. I literally have to stop, sit down, and catch my breath.

This train trip was about much more than media and public spectacle. For Christine Augustine, who drew that picture and wrote those words, for the woman who handed me the quilt, for the First Nation near Sioux Lookout, ON which contributed a blanket that was, as they said, infected with the indigenous justice virus, this train trip was about making something new. It was about building a new relationship. And there were risks. People who had been systematically abused by society and the church were willing to take the church at its word when it said, “we want to do what’s right.”

That trust, embodied for me in the commandment to “look after our blanket” is also a responsibility. I wasn’t shaken by the exchange in Moncton because it was some kind of dare. I was shaken because one of those people I was so unsure of meeting chose to meet me on equal terms. She accepted my reasons for being there and decided to hold me accountable. She had expectations of our meeting that went beyond the train platform, beyond the next day’s action at the Supreme Court, and demanded of me a commitment to the long haul. Now it’s up to me to figure out how I live out that commitment.